The Mechanics of Movement in Games

The Mechanics of Movement in Games is important!

The year is 1996, you’re playing Tomb Raider on PlayStation, and you need to jump between 2 platforms. What do you do? First you have to line up the jump by walking to the edge. Then you have to give yourself a run up. You then sprint to the edge of the platform and hold the jump button knowing that Lara will leap after exactly 2 more steps, then in mid air you have to hold a different button to reach out and grab the other platform. You must keep this button held as Lara Pulls herself up on the other side. That’s a stark difference to the way Lara moves in her more recent games. She now has a media acceleration and an ultra-responsive jump, so you don’t need to run up anymore. You can move her in mid air, so you don’t need to line up the jump. She automatically reaches out for platforms and grabs them, so you don’t need to press another button.

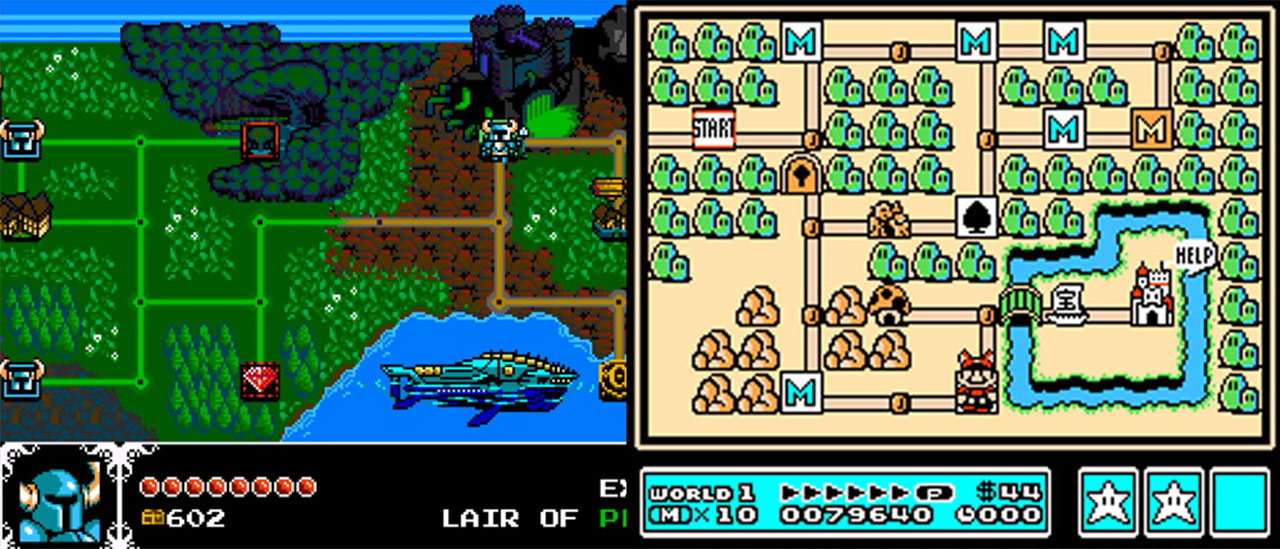

To some, the old way will seem clunky and frustrating. The more modern controls, which were brought in when Crystal Dynamics rebooted the series with Tomb Raider: Legend, a much more palatable and accessible. Of course there’s a lot of truth to that. Tomb Raider 1 operated on an unrealistic grid system. It was designed for a digital input, and it was the result of a developer’s first unrefined grasp at working in a 3D space.

I think we also lost something in the transition to the ultra-simple traversal controls we see in games like Rise of the Tomb Raider and Uncharted. The old system demanded expertise. You became a master of the controls, like how you learn to subconsciously flick-trick in and out a very grind and manual in Tony Hawks. You had to act deliberately and with intention, like dare I say it, Dark Souls. In Tomb Raider leap across a giant chasm is almost as terrifying and rewarding as it would be in real life. Whereas that exact same jump in the decade later remake Tomb Raider: Anniversary is so bereft of challenge that you barely even register that it happened.

“The old system demanded expertise. You became a master of the controls…”

The slow decline of mechanical sophistication in Tomb Raider is traversal. From adding annoying automated movements like monkey bars, to removing the need to hold grab, to removing the need for a run up, looks even worse when you compare it to the way the Franchise’s Combat has evolved. We’ve gone from wildly firing at bats, to doing stealth kills, making head shots, taking cover, readying arrows, making and throwing bombs, destructing enemies, pulling down structures, and juggling different ammo types. These mechanics make Combat and Tomb Raider dynamic and interesting. You have to consider your options and figure out which strategy to use on which enemy. You can improve your abilities by through upgrades and just practice. You need dexterity and to remember complicated control schemes, and it’s rewarding when you successful kill a bunch of baddies. Traversal has become practically automated. Jump at the colored ledge, hold her direction, press jump, hold her direction. Surely we can do something more interesting than this.

Thankfully we can. A number of smaller games show us that movement can still be as deep and involving as like murdering a dude. Perhaps the most obvious example is first person parkour game, Mirror’s Edge. This game is all about movement, and you have so much control of the way protagonist Faith moves through the world. She has acceleration on her run so she can jump further after she has built up speed. She can tuck mid-jump to clear high fences and roll when she hits the ground to avoid fall damage. Her large repertoire of moves gives you more options when moving through a space. In this alley section you can run up the stairs like a damn chump or you can bounce off the wall, and climb her up here, and volt over this bar to get to the same place in far less time.

For the most part the Assassin’s Creed Games heavily automate movement. The most recent entry Syndicate, you don’t even need to climb up buildings anymore as Evie Frye essentially pinched Batman’s grappling hook from Arkham City.

I’d be remiss not to point out the grasp mechanic in Assassin’s Creed II. While in mid air, Ezio can reach an arm out mid-jump to snatch at nearby ledges and ropes to avoid a nasty drop, or to take an alternative route. Experienced players can use this to give themselves more control when exploring the city’s rooftops.

Ubisoft’s experimental game, Grow Home, has got this great climbing system where the two triggers are used to grab with your two robot hands, and you must do that carefully and rhythmically to climb up these massive plants. As you get higher and higher, and nervously wobble along these thin branches, it gets genuinely quite tense. Compare that to climbing this massive tower in Tomb Raider 2013, which you heroically scaled by holding up on the analogue stick. Lara might look terrified, but trust me you won’t be.

One of the reasons Grow Home works is because hero BUD is animated in real-time instead of using pre-canned animations. That’s the secret behind the mad flash game Gurk II, because this game is all about building momentum as you tense your muscles to lunge yourself towards the next handhold. The shirtless ginger climber must be able to bend and flex in all sorts of directions. The game also benefits from an absurd control scheme, where you have to hold various letters on the keyboard to clime. Developer Bennett Foddy told Wired that he intentionally made players “Grip the keyboard just like you would cling to the cliff”, and says his games tap into “A kind of neurological magic which makes you feel like you are the character, rather than just controlling a little guy on the screen.

You can go even further than that with the genuinely, quite brilliant, and utterly exhausting Rock ‘N Roll Climber for WiiWare, which has you gripping and releasing different buttons on the remote and Nunchuck, and then physically reaching out to scale a cliff. Once at the top you play some air guitar, obviously.

If you don’t want to go quite so literal in your climbing metaphor perhaps look to a different Ubisoft game, I Am Alive, where your character has a stamina meter that depletes when you climb up buildings. You expend more if you jump while climbing, and if you use up the whole meter you go into a tense last ditch scramble that leaves a lasting impact on your stamina bar. This like the grip meter in Shadow of the Colossus, makes you think more carefully about how you’ll approach climbing in the game.

What all these games do is prove that climbing can be challenging and a nuance. By asking you to consider things like momentum, inertia, and grip strength, they prove that traversal can actually be a mechanic that’s very bit as deep as combat. They also give you options. Where the route for a room in Rise of the Tomb Raider is often linear and prescribed, these games ask you whether you want to take the slow and easy route or the fast and dangerous one, and provide a tangible sense of reward when you pull off the tricky combination of moves, and perfectly-timed button presses that the hard road requires. Many of them use their controls to make you feel closer to the action on screen, and use real-time animation to capture the dynamic and analogue nature of scrambling up a wall.

If Lara Croft wants to trade in climb ring for killing, that’s her business. You do you, Lara, I’ll find my fun in the Challenge Tombs. For a second imagine the Tomb Raider Game with the physics of Mirror’s Edge, the tense grip meter of I Am Alive, and the hand over hand climbing of Grow Home, and just try and tell me that it doesn’t make you a little bit excited.

Visit Mark at Game Maker’s ToolKit on YouTube to see more awesome videos like this!